Category: Artificial Intelligence

-

Meta AI 'personalized' chatbot revives privacy fears

Meta AI says it provides personalized answers and advice using data about ‘your interests, location, profile, and activity on Meta products.’ -

Capital intensity will reprogram Big Tech values

Big Tech is attempting the mother of all pivots. Although startups from Twitter to Instagram are renowned for remaking their businesses on the fly, none compares to the scale of the transformations underway at Microsoft and other software giants that historically steered clear of owning too much property or equipment. They are now pouring resources into physical assets, jeopardizing profitability and rich valuations in the process. -

Designers are excited about AI, but most don’t know what to do with it

Figma’s new annual report on the state of generative AI for designers and developers shows how messy the transition to artificial intelligence can be. -

Proposed CT artificial intelligence law moves forward

Seeking safeguards on one of the world’s fastest-moving industries, a key legislative committee voted to provide oversight of artificial intelligence.

Subscribe to continue reading this article.

Already subscribed? To log in, click here.

-

Proposed CT artificial intelligence law moves forward. Why there’s so much opposition to it.

Seeking safeguards on one of the world’s fastest-moving industries, a key legislative committee voted to provide oversight of artificial intelligence. The judiciary committee voted 28-11, largely along party lines, for a measure pushed by Democrats to curb potential excesses of artificial intelligence. But Gov. Ned Lamont and Republicans have opposed the idea, saying they do not want to stifle … -

How to Use A.I.-Powered Writing Tools on Your iPhone and Android

Artificial intelligence software has given editing tools a huge boost in power, far beyond the spell-checkers and grammar aids of yore.

A.I. can proofread, rewrite, summarize and compose text, making it simple to craft clean, complex documents in a flash — even on a smartphone. If you haven’t dabbled yet, free offerings from Apple and Google are an easy place to begin experimenting.

Tinkering with the software lets you see its capabilities and gives you insight on when — and when not — to let A.I. do the writing. Here’s a guide to getting started.

Using Apple Intelligence

Apple’s integrated suite of A.I. tools, called Apple Intelligence, includes a selection of Writing Tools. (It requires iOS 18.1 and a more recent iPhone or iPad.)

The Writing Tools work in most apps where you type or dictate words. Once you have written something (like in Pages), highlight the section you want to edit. Select Writing Tools in the pop-up menu, or tap the circular Apple Intelligence icon in the toolbar.

In the Writing Tools menu, select the option you want to use, like Proofread, Rewrite or Summarize — or describe how you want to change the text. You can display it as key points, a list or a table, or even recast the tone of the writing with a tap to make it sound friendlier, more professional or streamlined. If you don’t like the changes, revert to the original.

With the help of the popular ChatGPT chatbot, Apple Intelligence can compose a draft from scratch, although you need to enable ChatGPT first. To do so, tap the Compose button and follow the onscreen directions. (The New York Times has sued ChatGPT maker OpenAI and its partner, Microsoft, claiming copyright infringement of news content related to A.I. systems. The two companies have denied the suit’s claims.)

Like other A.I. chatbots, Gemini responds to questions and prompts. For example, you could paste in a memo draft and ask Gemini to proofread and fact-check it for you.

Gemini can also generate text upon request, like a project proposal. For example, in the prompt box, enter “Help me draft a proposal to the City Council to get a permit for a Dog Days of Summer festival on Aug. 2 and 3 that features a puppy parade, a Wiener Dog Derby, a fetch competition and vendor booths for local pet stores.”

Once Gemini cranks out the proposal draft, you can save it as a Google Doc for your own editing and refinement.

Using Other Options

If your device is too old for Apple Intelligence or you don’t use Google products, you still have plenty of A.I. helpers to consider, although many charge a subscription fee. Grammerly has been around since 2009 and now has a mobile app that works with your device’s keyboard software for proofreading, tone adjustments and other A.I. assistance. Microsoft has its Copilot A.I. tool that works with the Microsoft 365 suite.

The app stores have many A.I. bots, including writing-specific assistants like ParagraphAI for a variety of communications styles (including help for dyslexic writers) and Sudowrite for narrative projects. General chatbots like ChatGPT (which has a writing assistant) or Anthropic’s Claude can rewrite or generate text.

Keep in Mind

Remember that A.I. is not perfect. Check the bot’s work because it can make mistakes.

And while A.I. assistance has numerous advantages for more impersonal documents like memos and proposals, relying on it too much can dilute your voice and style — especially as more people use A.I. to write.

Take the first sentences of Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1891 short story “A Scandal in Bohemia,” as rewritten by software to make Dr. Watson sound more casual:

Original: To Sherlock Holmes she is always the woman. I have seldom heard him mention her under any other name. In his eyes she eclipses and predominates the whole of her sex. It was not that he felt any emotion akin to love for Irene Adler.

Apple Intelligence: Sherlock Holmes always referred to her as the woman. He rarely used any other name for her. In his mind, she was the most prominent woman among all women. It wasn’t because he felt any romantic feelings for Irene Adler.

Gemini: For Sherlock, she’s always just ‘the woman.’ I’ve hardly ever heard him call her anything else. The way he sees it, she totally outshines all other women. It’s not like he was in love with Irene Adler or anything.

You should always be in command of your own words — which might help prevent people from thinking, “Hey, did A.I. write this?”

-

Rampant AI Cheating Is Ruining Education Alarmingly Fast

Illustration: New York Magazine

Chungin “Roy” Lee stepped onto Columbia University’s campus this past fall and, by his own admission, proceeded to use generative artificial intelligence to cheat on nearly every assignment. As a computer-science major, he depended on AI for his introductory programming classes: “I’d just dump the prompt into ChatGPT and hand in whatever it spat out.” By his rough math, AI wrote 80 percent of every essay he turned in. “At the end, I’d put on the finishing touches. I’d just insert 20 percent of my humanity, my voice, into it,” Lee told me recently.

Lee was born in South Korea and grew up outside Atlanta, where his parents run a college-prep consulting business. He said he was admitted to Harvard early in his senior year of high school, but the university rescinded its offer after he was suspended for sneaking out during an overnight field trip before graduation. A year later, he applied to 26 schools; he didn’t get into any of them. So he spent the next year at a community college, before transferring to Columbia. (His personal essay, which turned his winding road to higher education into a parable for his ambition to build companies, was written with help from ChatGPT.) When he started at Columbia as a sophomore this past September, he didn’t worry much about academics or his GPA. “Most assignments in college are not relevant,” he told me. “They’re hackable by AI, and I just had no interest in doing them.” While other new students fretted over the university’s rigorous core curriculum, described by the school as “intellectually expansive” and “personally transformative,” Lee used AI to breeze through with minimal effort. When I asked him why he had gone through so much trouble to get to an Ivy League university only to off-load all of the learning to a robot, he said, “It’s the best place to meet your co-founder and your wife.”

By the end of his first semester, Lee checked off one of those boxes. He met a co-founder, Neel Shanmugam, a junior in the school of engineering, and together they developed a series of potential start-ups: a dating app just for Columbia students, a sales tool for liquor distributors, and a note-taking app. None of them took off. Then Lee had an idea. As a coder, he had spent some 600 miserable hours on LeetCode, a training platform that prepares coders to answer the algorithmic riddles tech companies ask job and internship candidates during interviews. Lee, like many young developers, found the riddles tedious and mostly irrelevant to the work coders might actually do on the job. What was the point? What if they built a program that hid AI from browsers during remote job interviews so that interviewees could cheat their way through instead?

In February, Lee and Shanmugam launched a tool that did just that. Interview Coder’s website featured a banner that read F*CK LEETCODE. Lee posted a video of himself on YouTube using it to cheat his way through an internship interview with Amazon. (He actually got the internship, but turned it down.) A month later, Lee was called into Columbia’s academic-integrity office. The school put him on disciplinary probation after a committee found him guilty of “advertising a link to a cheating tool” and “providing students with the knowledge to access this tool and use it how they see fit,” according to the committee’s report.

Lee thought it absurd that Columbia, which had a partnership with ChatGPT’s parent company, OpenAI, would punish him for innovating with AI. Although Columbia’s policy on AI is similar to that of many other universities’ — students are prohibited from using it unless their professor explicitly permits them to do so, either on a class-by-class or case-by-case basis — Lee said he doesn’t know a single student at the school who isn’t using AI to cheat. To be clear, Lee doesn’t think this is a bad thing. “I think we are years — or months, probably — away from a world where nobody thinks using AI for homework is considered cheating,” he said.

In January 2023, just two months after OpenAI launched ChatGPT, a survey of 1,000 college students found that nearly 90 percent of them had used the chatbot to help with homework assignments. In its first year of existence, ChatGPT’s total monthly visits steadily increased month-over-month until June, when schools let out for the summer. (That wasn’t an anomaly: Traffic dipped again over the summer in 2024.) Professors and teaching assistants increasingly found themselves staring at essays filled with clunky, robotic phrasing that, though grammatically flawless, didn’t sound quite like a college student — or even a human. Two and a half years later, students at large state schools, the Ivies, liberal-arts schools in New England, universities abroad, professional schools, and community colleges are relying on AI to ease their way through every facet of their education. Generative-AI chatbots — ChatGPT but also Google’s Gemini, Anthropic’s Claude, Microsoft’s Copilot, and others — take their notes during class, devise their study guides and practice tests, summarize novels and textbooks, and brainstorm, outline, and draft their essays. STEM students are using AI to automate their research and data analyses and to sail through dense coding and debugging assignments. “College is just how well I can use ChatGPT at this point,” a student in Utah recently captioned a video of herself copy-and-pasting a chapter from her Genocide and Mass Atrocity textbook into ChatGPT.

Sarah, a freshman at Wilfrid Laurier University in Ontario, said she first used ChatGPT to cheat during the spring semester of her final year of high school. (Sarah’s name, like those of other current students in this article, has been changed for privacy.) After getting acquainted with the chatbot, Sarah used it for all her classes: Indigenous studies, law, English, and a “hippie farming class” called Green Industries. “My grades were amazing,” she said. “It changed my life.” Sarah continued to use AI when she started college this past fall. Why wouldn’t she? Rarely did she sit in class and not see other students’ laptops open to ChatGPT. Toward the end of the semester, she began to think she might be dependent on the website. She already considered herself addicted to TikTok, Instagram, Snapchat, and Reddit, where she writes under the username maybeimnotsmart. “I spend so much time on TikTok,” she said. “Hours and hours, until my eyes start hurting, which makes it hard to plan and do my schoolwork. With ChatGPT, I can write an essay in two hours that normally takes 12.”

Teachers have tried AI-proofing assignments, returning to Blue Books or switching to oral exams. Brian Patrick Green, a tech-ethics scholar at Santa Clara University, immediately stopped assigning essays after he tried ChatGPT for the first time. Less than three months later, teaching a course called Ethics and Artificial Intelligence, he figured a low-stakes reading reflection would be safe — surely no one would dare use ChatGPT to write something personal. But one of his students turned in a reflection with robotic language and awkward phrasing that Green knew was AI-generated. A philosophy professor across the country at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock caught students in her Ethics and Technology class using AI to respond to the prompt “Briefly introduce yourself and say what you’re hoping to get out of this class.”

It isn’t as if cheating is new. But now, as one student put it, “the ceiling has been blown off.” Who could resist a tool that makes every assignment easier with seemingly no consequences? After spending the better part of the past two years grading AI-generated papers, Troy Jollimore, a poet, philosopher, and Cal State Chico ethics professor, has concerns. “Massive numbers of students are going to emerge from university with degrees, and into the workforce, who are essentially illiterate,” he said. “Both in the literal sense and in the sense of being historically illiterate and having no knowledge of their own culture, much less anyone else’s.” That future may arrive sooner than expected when you consider what a short window college really is. Already, roughly half of all undergrads have never experienced college without easy access to generative AI. “We’re talking about an entire generation of learning perhaps significantly undermined here,” said Green, the Santa Clara tech ethicist. “It’s short-circuiting the learning process, and it’s happening fast.”

Before OpenAI released ChatGPT in November 2022, cheating had already reached a sort of zenith. At the time, many college students had finished high school remotely, largely unsupervised, and with access to tools like Chegg and Course Hero. These companies advertised themselves as vast online libraries of textbooks and course materials but, in reality, were cheating multi-tools. For $15.95 a month, Chegg promised answers to homework questions in as little as 30 minutes, 24/7, from the 150,000 experts with advanced degrees it employed, mostly in India. When ChatGPT launched, students were primed for a tool that was faster, more capable.

But school administrators were stymied. There would be no way to enforce an all-out ChatGPT ban, so most adopted an ad hoc approach, leaving it up to professors to decide whether to allow students to use AI. Some universities welcomed it, partnering with developers, rolling out their own chatbots to help students register for classes, or launching new classes, certificate programs, and majors focused on generative AI. But regulation remained difficult. How much AI help was acceptable? Should students be able to have a dialogue with AI to get ideas but not ask it to write the actual sentences?

These days, professors will often state their policy on their syllabi — allowing AI, for example, as long as students cite it as if it were any other source, or permitting it for conceptual help only, or requiring students to provide receipts of their dialogue with a chatbot. Students often interpret those instructions as guidelines rather than hard rules. Sometimes they will cheat on their homework without even knowing — or knowing exactly how much — they are violating university policy when they ask a chatbot to clean up a draft or find a relevant study to cite. Wendy, a freshman finance major at one of the city’s top universities, told me that she is against using AI. Or, she clarified, “I’m against copy-and-pasting. I’m against cheating and plagiarism. All of that. It’s against the student handbook.” Then she described, step-by-step, how on a recent Friday at 8 a.m., she called up an AI platform to help her write a four-to-five-page essay due two hours later.

Whenever Wendy uses AI to write an essay (which is to say, whenever she writes an essay), she follows three steps. Step one: “I say, ‘I’m a first-year college student. I’m taking this English class.’” Otherwise, Wendy said, “it will give you a very advanced, very complicated writing style, and you don’t want that.” Step two: Wendy provides some background on the class she’s taking before copy-and-pasting her professor’s instructions into the chatbot. Step three: “Then I ask, ‘According to the prompt, can you please provide me an outline or an organization to give me a structure so that I can follow and write my essay?’ It then gives me an outline, introduction, topic sentences, paragraph one, paragraph two, paragraph three.” Sometimes, Wendy asks for a bullet list of ideas to support or refute a given argument: “I have difficulty with organization, and this makes it really easy for me to follow.”

Once the chatbot had outlined Wendy’s essay, providing her with a list of topic sentences and bullet points of ideas, all she had to do was fill it in. Wendy delivered a tidy five-page paper at an acceptably tardy 10:17 a.m. When I asked her how she did on the assignment, she said she got a good grade. “I really like writing,” she said, sounding strangely nostalgic for her high-school English class — the last time she wrote an essay unassisted. “Honestly,” she continued, “I think there is beauty in trying to plan your essay. You learn a lot. You have to think, Oh, what can I write in this paragraph? Or What should my thesis be? ” But she’d rather get good grades. “An essay with ChatGPT, it’s like it just gives you straight up what you have to follow. You just don’t really have to think that much.”

I asked Wendy if I could read the paper she turned in, and when I opened the document, I was surprised to see the topic: critical pedagogy, the philosophy of education pioneered by Paulo Freire. The philosophy examines the influence of social and political forces on learning and classroom dynamics. Her opening line: “To what extent is schooling hindering students’ cognitive ability to think critically?” Later, I asked Wendy if she recognized the irony in using AI to write not just a paper on critical pedagogy but one that argues learning is what “makes us truly human.” She wasn’t sure what to make of the question. “I use AI a lot. Like, every day,” she said. “And I do believe it could take away that critical-thinking part. But it’s just — now that we rely on it, we can’t really imagine living without it.”

Most of the writing professors I spoke to told me that it’s abundantly clear when their students use AI. Sometimes there’s a smoothness to the language, a flattened syntax; other times, it’s clumsy and mechanical. The arguments are too evenhanded — counterpoints tend to be presented just as rigorously as the paper’s central thesis. Words like multifaceted and context pop up more than they might normally. On occasion, the evidence is more obvious, as when last year a teacher reported reading a paper that opened with “As an AI, I have been programmed …” Usually, though, the evidence is more subtle, which makes nailing an AI plagiarist harder than identifying the deed. Some professors have resorted to deploying so-called Trojan horses, sticking strange phrases, in small white text, in between the paragraphs of an essay prompt. (The idea is that this would theoretically prompt ChatGPT to insert a non sequitur into the essay.) Students at Santa Clara recently found the word broccoli hidden in a professor’s assignment. Last fall, a professor at the University of Oklahoma sneaked the phrases “mention Finland” and “mention Dua Lipa” in his. A student discovered his trap and warned her classmates about it on TikTok. “It does work sometimes,” said Jollimore, the Cal State Chico professor. “I’ve used ‘How would Aristotle answer this?’ when we hadn’t read Aristotle. But I’ve also used absurd ones and they didn’t notice that there was this crazy thing in their paper, meaning these are people who not only didn’t write the paper but also didn’t read their own paper before submitting it.”

Still, while professors may think they are good at detecting AI-generated writing, studies have found they’re actually not. One, published in June 2024, used fake student profiles to slip 100 percent AI-generated work into professors’ grading piles at a U.K. university. The professors failed to flag 97 percent. It doesn’t help that since ChatGPT’s launch, AI’s capacity to write human-sounding essays has only gotten better. Which is why universities have enlisted AI detectors like Turnitin, which uses AI to recognize patterns in AI-generated text. After evaluating a block of text, detectors provide a percentage score that indicates the alleged likelihood it was AI-generated. Students talk about professors who are rumored to have certain thresholds (25 percent, say) above which an essay might be flagged as an honor-code violation. But I couldn’t find a single professor — at large state schools or small private schools, elite or otherwise — who admitted to enforcing such a policy. Most seemed resigned to the belief that AI detectors don’t work. It’s true that different AI detectors have vastly different success rates, and there is a lot of conflicting data. While some claim to have less than a one percent false-positive rate, studies have shown they trigger more false positives for essays written by neurodivergent students and students who speak English as a second language. Turnitin’s chief product officer, Annie Chechitelli, told me that the product is tuned to err on the side of caution, more inclined to trigger a false negative than a false positive so that teachers don’t wrongly accuse students of plagiarism. I fed Wendy’s essay through a free AI detector, ZeroGPT, and it came back as 11.74 AI-generated, which seemed low given that AI, at the very least, had generated her central arguments. I then fed a chunk of text from the Book of Genesis into ZeroGPT and it came back as 93.33 percent AI-generated.

There are, of course, plenty of simple ways to fool both professors and detectors. After using AI to produce an essay, students can always rewrite it in their own voice or add typos. Or they can ask AI to do that for them: One student on TikTok said her preferred prompt is “Write it as a college freshman who is a li’l dumb.” Students can also launder AI-generated paragraphs through other AIs, some of which advertise the “authenticity” of their outputs or allow students to upload their past essays to train the AI in their voice. “They’re really good at manipulating the systems. You put a prompt in ChatGPT, then put the output into another AI system, then put it into another AI system. At that point, if you put it into an AI-detection system, it decreases the percentage of AI used every time,” said Eric, a sophomore at Stanford.

Most professors have come to the conclusion that stopping rampant AI abuse would require more than simply policing individual cases and would likely mean overhauling the education system to consider students more holistically. “Cheating correlates with mental health, well-being, sleep exhaustion, anxiety, depression, belonging,” said Denise Pope, a senior lecturer at Stanford and one of the world’s leading student-engagement researchers.

Many teachers now seem to be in a state of despair. In the fall, Sam Williams was a teaching assistant for a writing-intensive class on music and social change at the University of Iowa that, officially, didn’t allow students to use AI at all. Williams enjoyed reading and grading the class’s first assignment: a personal essay that asked the students to write about their own music tastes. Then, on the second assignment, an essay on the New Orleans jazz era (1890 to 1920), many of his students’ writing styles changed drastically. Worse were the ridiculous factual errors. Multiple essays contained entire paragraphs on Elvis Presley (born in 1935). “I literally told my class, ‘Hey, don’t use AI. But if you’re going to cheat, you have to cheat in a way that’s intelligent. You can’t just copy exactly what it spits out,’” Williams said.

Williams knew most of the students in this general-education class were not destined to be writers, but he thought the work of getting from a blank page to a few semi-coherent pages was, above all else, a lesson in effort. In that sense, most of his students utterly failed. “They’re using AI because it’s a simple solution and it’s an easy way for them not to put in time writing essays. And I get it, because I hated writing essays when I was in school,” Williams said. “But now, whenever they encounter a little bit of difficulty, instead of fighting their way through that and growing from it, they retreat to something that makes it a lot easier for them.”

By November, Williams estimated that at least half of his students were using AI to write their papers. Attempts at accountability were pointless. Williams had no faith in AI detectors, and the professor teaching the class instructed him not to fail individual papers, even the clearly AI-smoothed ones. “Every time I brought it up with the professor, I got the sense he was underestimating the power of ChatGPT, and the departmental stance was, ‘Well, it’s a slippery slope, and we can’t really prove they’re using AI,’” Williams said. “I was told to grade based on what the essay would’ve gotten if it were a ‘true attempt at a paper.’ So I was grading people on their ability to use ChatGPT.”

The “true attempt at a paper” policy ruined Williams’s grading scale. If he gave a solid paper that was obviously written with AI a B, what should he give a paper written by someone who actually wrote their own paper but submitted, in his words, “a barely literate essay”? The confusion was enough to sour Williams on education as a whole. By the end of the semester, he was so disillusioned that he decided to drop out of graduate school altogether. “We’re in a new generation, a new time, and I just don’t think that’s what I want to do,” he said.

Jollimore, who has been teaching writing for more than two decades, is now convinced that the humanities, and writing in particular, are quickly becoming an anachronistic art elective like basket-weaving. “Every time I talk to a colleague about this, the same thing comes up: retirement. When can I retire? When can I get out of this? That’s what we’re all thinking now,” he said. “This is not what we signed up for.” Williams, and other educators I spoke to, described AI’s takeover as a full-blown existential crisis. “The students kind of recognize that the system is broken and that there’s not really a point in doing this. Maybe the original meaning of these assignments has been lost or is not being communicated to them well.”

He worries about the long-term consequences of passively allowing 18-year-olds to decide whether to actively engage with their assignments. Would it accelerate the widening soft-skills gap in the workplace? If students rely on AI for their education, what skills would they even bring to the workplace? Lakshya Jain, a computer-science lecturer at the University of California, Berkeley, has been using those questions in an attempt to reason with his students. “If you’re handing in AI work,” he tells them, “you’re not actually anything different than a human assistant to an artificial-intelligence engine, and that makes you very easily replaceable. Why would anyone keep you around?” That’s not theoretical: The COO of a tech research firm recently asked Jain why he needed programmers any longer.

The ideal of college as a place of intellectual growth, where students engage with deep, profound ideas, was gone long before ChatGPT. The combination of high costs and a winner-takes-all economy had already made it feel transactional, a means to an end. (In a recent survey, Deloitte found that just over half of college graduates believe their education was worth the tens of thousands of dollars it costs a year, compared with 76 percent of trade-school graduates.) In a way, the speed and ease with which AI proved itself able to do college-level work simply exposed the rot at the core. “How can we expect them to grasp what education means when we, as educators, haven’t begun to undo the years of cognitive and spiritual damage inflicted by a society that treats schooling as a means to a high-paying job, maybe some social status, but nothing more?” Jollimore wrote in a recent essay. “Or, worse, to see it as bearing no value at all, as if it were a kind of confidence trick, an elaborate sham?”

It’s not just the students: Multiple AI platforms now offer tools to leave AI-generated feedback on students’ essays. Which raises the possibility that AIs are now evaluating AI-generated papers, reducing the entire academic exercise to a conversation between two robots — or maybe even just one.

It’ll be years before we can fully account for what all of this is doing to students’ brains. Some early research shows that when students off-load cognitive duties onto chatbots, their capacity for memory, problem-solving, and creativity could suffer. Multiple studies published within the past year have linked AI usage with a deterioration in critical-thinking skills; one found the effect to be more pronounced in younger participants. In February, Microsoft and Carnegie Mellon University published a study that found a person’s confidence in generative AI correlates with reduced critical-thinking effort. The net effect seems, if not quite Wall-E, at least a dramatic reorganization of a person’s efforts and abilities, away from high-effort inquiry and fact-gathering and toward integration and verification. This is all especially unnerving if you add in the reality that AI is imperfect — it might rely on something that is factually inaccurate or just make something up entirely — with the ruinous effect social media has had on Gen Z’s ability to tell fact from fiction. The problem may be much larger than generative AI. The so-called Flynn effect refers to the consistent rise in IQ scores from generation to generation going back to at least the 1930s. That rise started to slow, and in some cases reverse, around 2006. “The greatest worry in these times of generative AI is not that it may compromise human creativity or intelligence,” Robert Sternberg, a psychology professor at Cornell University, told The Guardian, “but that it already has.”

Students are worrying about this, even if they’re not willing or able to give up the chatbots that are making their lives exponentially easier. Daniel, a computer-science major at the University of Florida, told me he remembers the first time he tried ChatGPT vividly. He marched down the hall to his high-school computer-science teacher’s classroom, he said, and whipped out his Chromebook to show him. “I was like, ‘Dude, you have to see this!’ My dad can look back on Steve Jobs’s iPhone keynote and think, Yeah, that was a big moment. That’s what it was like for me, looking at something that I would go on to use every day for the rest of my life.”

AI has made Daniel more curious; he likes that whenever he has a question, he can quickly access a thorough answer. But when he uses AI for homework, he often wonders, If I took the time to learn that, instead of just finding it out, would I have learned a lot more? At school, he asks ChatGPT to make sure his essays are polished and grammatically correct, to write the first few paragraphs of his essays when he’s short on time, to handle the grunt work in his coding classes, to cut basically all cuttable corners. Sometimes, he knows his use of AI is a clear violation of student conduct, but most of the time it feels like he’s in a gray area. “I don’t think anyone calls seeing a tutor cheating, right? But what happens when a tutor starts writing lines of your paper for you?” he said.

Recently, Mark, a freshman math major at the University of Chicago, admitted to a friend that he had used ChatGPT more than usual to help him code one of his assignments. His friend offered a somewhat comforting metaphor: “You can be a contractor building a house and use all these power tools, but at the end of the day, the house won’t be there without you.” Still, Mark said, “it’s just really hard to judge. Is this my work? ” I asked Daniel a hypothetical to try to understand where he thought his work began and AI’s ended: Would he be upset if he caught a romantic partner sending him an AI-generated poem? “I guess the question is what is the value proposition of the thing you’re given? Is it that they created it? Or is the value of the thing itself?” he said. “In the past, giving someone a letter usually did both things.” These days, he sends handwritten notes — after he has drafted them using ChatGPT.

“Language is the mother, not the handmaiden, of thought,” wrote Duke professor Orin Starn in a recent column titled “My Losing Battle Against AI Cheating,” citing a quote often attributed to W. H. Auden. But it’s not just writing that develops critical thinking. “Learning math is working on your ability to systematically go through a process to solve a problem. Even if you’re not going to use algebra or trigonometry or calculus in your career, you’re going to use those skills to keep track of what’s up and what’s down when things don’t make sense,” said Michael Johnson, an associate provost at Texas A&M University. Adolescents benefit from structured adversity, whether it’s algebra or chores. They build self-esteem and work ethic. It’s why the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt has argued for the importance of children learning to do hard things, something that technology is making infinitely easier to avoid. Sam Altman, OpenAI’s CEO, has tended to brush off concerns about AI use in academia as shortsighted, describing ChatGPT as merely “a calculator for words” and saying the definition of cheating needs to evolve. “Writing a paper the old-fashioned way is not going to be the thing,” Altman, a Stanford dropout, said last year. But speaking before the Senate’s oversight committee on technology in 2023, he confessed his own reservations: “I worry that as the models get better and better, the users can have sort of less and less of their own discriminating process.” OpenAI hasn’t been shy about marketing to college students. It recently made ChatGPT Plus, normally a $20-per-month subscription, free to them during finals. (OpenAI contends that students and teachers need to be taught how to use it responsibly, pointing to the ChatGPT Edu product it sells to academic institutions.)

In late March, Columbia suspended Lee after he posted details about his disciplinary hearing on X. He has no plans to go back to school and has no desire to work for a big-tech company, either. Lee explained to me that by showing the world AI could be used to cheat during a remote job interview, he had pushed the tech industry to evolve the same way AI was forcing higher education to evolve. “Every technological innovation has caused humanity to sit back and think about what work is actually useful,” he said. “There might have been people complaining about machinery replacing blacksmiths in, like, the 1600s or 1800s, but now it’s just accepted that it’s useless to learn how to blacksmith.”

Lee has already moved on from hacking interviews. In April, he and Shanmugam launched Cluely, which scans a user’s computer screen and listens to its audio in order to provide AI feedback and answers to questions in real time without prompting. “We built Cluely so you never have to think alone again,” the company’s manifesto reads. This time, Lee attempted a viral launch with a $140,000 scripted advertisement in which a young software engineer, played by Lee, uses Cluely installed on his glasses to lie his way through a first date with an older woman. When the date starts going south, Cluely suggests Lee “reference her art” and provides a script for him to follow. “I saw your profile and the painting with the tulips. You are the most gorgeous girl ever,” Lee reads off his glasses, which rescues his chances with her.

Before launching Cluely, Lee and Shanmugam raised $5.3 million from investors, which allowed them to hire two coders, friends Lee met in community college (no job interviews or LeetCode riddles were necessary), and move to San Francisco. When we spoke a few days after Cluely’s launch, Lee was at his Realtor’s office and about to get the keys to his new workspace. He was running Cluely on his computer as we spoke. While Cluely can’t yet deliver real-time answers through people’s glasses, the idea is that someday soon it’ll run on a wearable device, seeing, hearing, and reacting to everything in your environment. “Then, eventually, it’s just in your brain,” Lee said matter-of-factly. For now, Lee hopes people will use Cluely to continue AI’s siege on education. “We’re going to target the digital LSATs; digital GREs; all campus assignments, quizzes, and tests,” he said. “It will enable you to cheat on pretty much everything.”

-

Bill Gates says AI key for health, education innovation

Credit: Pixabay/CC0 Public Domain

Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates said artificial intelligence will play a key role in unlocking new tools for health, education and agriculture at a meeting with Indonesia’s president on Wednesday.

Indonesia is Southeast Asia’s biggest economy and has a population of around 280 million across its sprawling archipelago, with a growing demand for data centers and AI tech in the region.

Gates visited President Prabowo Subianto and Indonesian philanthropists in the capital Jakarta, where he spoke about his optimism that AI-driven innovation will help tackle global challenges.

“AI is going to help us discover new tools. And even in the delivery of health and education and agriculture advice, we’ll be using AI,” he told a meeting.

“Once we finish (eradicating) polio, we’d like to try and eradicate measles and malaria as well. We have some new tools for that. And of course, part of my optimism about the innovation is because we have now artificial intelligence.”

UN agencies have been campaigning for four decades to eradicate polio, most often spread through sewage and contaminated water.

The billionaire philanthropist has donated more than $159 million to Indonesia since 2009, mostly to the health sector including to fund vaccines, Prabowo said.

Gates later visited an elementary school in Jakarta alongside Prabowo to see students having free meals as part of a program launched by the Indonesian leader.

Prabowo also announced plans to give Gates Indonesia’s highest civilian award for his “contribution to the Indonesian people and the world”.

Microsoft chief executive officer Satya Nadella last year pledged a $1.7 billion investment in AI and cloud computing to help develop Indonesia’s AI infrastructure.

© 2025 AFP

Citation:

Bill Gates says AI key for health, education innovation (2025, May 7)

retrieved 7 May 2025

from https://techxplore.com/news/2025-05-bill-gates-ai-key-health.htmlThis document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only. -

Amazon Has Made a Robot With a Sense of Touch

Amazon has developed a new warehouse robot that uses touch to rummage around shelves to find the right product to ship to customers.

The robot, called Vulcan, is a meaningful step towards making robots less sausage-fingered compared to human beings. Honing robots’ tactile abilities further may allow them to take on more fulfillment and manufacturing work in the years ahead.

Aaron Parness, Amazon’s director of robotics AI who led the development of Vulcan, explains that touch sensing helps the robot push items around on a shelf and identify what it’s after. “When you’re trying to stow [or pick] items in one of these pods, you can’t really do that task without making contact with the other items,” he says.

The Vulcan system consists of a conventional robotic arm with a custom spatula-like appendage for poking into a shelf, and a sucker for grabbing items to pull them out.

Vulcan has sensors on several of its joints that allow the robot to detect the edge and contours of items. Parness says that machine learning is key to making sense of the sensor signals and also forms part of the algorithmic loop that controls how a robot takes actions. “The special sauce we have is the software interpretation of the force torque, and how we wrap those into our control loop and into our motion plans,” he says.

Amazon revealed Vulcan at a fulfillment center in Hamburg, Germany today. The company says the robot is already working at this facility and another in Spokane, Washington.

The new robots will work on the same line as human pickers, and will aim to spare them from back-aching work by grasping more items from shelves that are high up or low down. Items that the robot decides it cannot find will be reassigned to human workers.

“Amazon stores many different products in bins, so rummaging is necessary to pull out a specific object to fill an order,” says Ken Goldberg, a roboticist at the University of California, Berkeley. “Until now this has been very difficult, so I’m curious to see the new system.”

Goldberg says that research on robotic touch sensing has advanced in recent years, with numerous groups working on joint and surface sensing. But he added that robots have some way to go before they can match the tactile abilities of flesh-and-blood workers. “The human sense of touch is extremely sensitive and complex, with a huge dynamic range,” Goldberg says. “Robots are progressing rapidly but I’d be surprised to see human-equivalent [skin] sensors in the next five-to-ten years.”

Robot coworkers

Even so, Vulcan should help automate more of the work currently done by humans inside Amazon’s vast empire of fulfillment centers. The company has ramped up automation in recent years with AI-infused robots capable of grabbing and transporting packages and packed boxes. Stowing and retrieving items from shelves is one of the more challenging jobs for robots to do, and it is heavily dependent on human labor.

Parness says he does not foresee robots taking on all of the work done inside Amazon’s fulfillment centers. “We don’t really believe in 100 percent automation, or lights out fulfillment,” he says. “We can get to 75 percent and have robots working alongside our employees, and the sum would be greater [than either working alone].”

-

Prediction: 5 Stocks That’ll Be Worth More Than Artificial Intelligence (AI) Stock Nvidia 3 Years From Now

If the AI bubble bursts, five highly influential, market-leading businesses can leapfrog Nvidia in value.

Since the start of 2023, there hasn’t been a hotter trend on Wall Street than the evolution of artificial intelligence (AI). Empowering software and systems with tools that allow them to reason and act on their own, and potentially even learn new jobs and skillsets without the need for human oversight, is a game-changing innovation with a big addressable market.

While estimates of just how much AI can contribute to economic growth are all over the map, PwC pegged its global addressable market at a cool $15.7 trillion by 2030. If the actual impact of artificial intelligence is anywhere in the ballpark of this figure, there are going to be multiple winners.

Image source: Getty Images.

Thus far, no company has more directly benefited from the rise of AI than Nvidia (NVDA -0.02%). Its valuation climbed from $360 billion to end 2022 to well north of $3 trillion in less than two years. Nvidia’s Hopper (H100) graphics processing unit (GPU) and next-generation Blackwell GPU architecture have been the preferred chips used by businesses wanting to be on the leading edge of AI innovation.

The grim reality: Nvidia might be in a bubble

But there’s also a realistic chance Nvidia is in a bubble, which would allow other influential businesses nipping at its heels to leapfrog it in the valuation department.

To begin with, there hasn’t been a game-changing innovation, technology, or trend for more than three decades that’s avoided a bubble-bursting event in its early expansion phase. This is to say that investors frequently overestimate early adoption rates and the broad-based utility of highly touted technologies and innovations. Eventually, it leads to lofty expectations not being met. If an AI bubble were to form and burst, it would undoubtedly hit Nvidia stock hard.

Competition is also mounting in the AI-GPU space — albeit from an unlikely source. Though direct competitors are ramping up production of high-powered chips for enterprise data centers, the biggest worry might be that most of Nvidia’s top customers by net sales are internally developing chips of their own to use in their data centers.

Even if these AI-GPUs lack the compute potential of Nvidia’s hardware, they’ll be notably cheaper and not backlogged. There’s a very real possibility of Nvidia losing out on future orders, or at the very least losing its premium pricing power.

I’d expect these headwinds to weigh down Nvidia stock over the coming three years and allow the following five companies to surpass its market cap. Note, I’m excluding Microsoft and Apple since their market caps are already higher than Nvidia, as of this writing.

1. Amazon

The likeliest of all companies to surpass Nvidia’s valuation at some point over the next three years is e-commerce colossus Amazon (AMZN -0.48%). I’d argue Amazon is on a trajectory that could make it the largest publicly traded company by the turn of the decade.

While most people are familiar with Amazon because of its globally dominant online marketplace, its growth engine is primarily tied to its cloud infrastructure service platform, Amazon Web Services (AWS). AWS accounted for a third of all cloud infrastructure service spend during the fourth quarter of 2024, based on estimates from Canalys. More importantly, it’s growing by a high-teens percentage on a year-over-year basis, with $117 billion in high-margin, annual run-rate sales.

Amazon’s other high-growth ancillary segments aren’t slouches, either. Being one of the premier social media destinations has made it an advertising rockstar. Even in a challenging economic environment, advertising services revenue is climbing by nearly 20% on a constant-currency basis. When coupled with the exceptional pricing power of Prime subscriptions, Amazon has the tools to generate outsized cash flow growth over the next three-to-five years, if not well beyond.

2. Alphabet

Google parent Alphabet (GOOGL -0.42%) (GOOG -0.34%) is a second stock that has the catalysts to leapfrog Nvidia in the next three years.

Similar to Amazon, Alphabet is leaning on its cloud infrastructure service platform (Google Cloud) to ramp up its growth potential and operating cash flow. Google Cloud is incorporating artificial intelligence to give its clients access to generative AI solutions and large language model tools. This high-margin segment has been recurringly profitable for Alphabet since 2023, and is generating around $49 billion in annual run-rate sales, as of the March-ended quarter.

But even though Alphabet is relying on AI to supercharge its high-margin growth rate, it has a foundational cash cow to fall back on in the event the AI bubble bursts. Google operates as a near-monopoly in global internet search, with just shy of a 90% share, as of April 2025, per GlobalStats. Disproportionately long economic growth cycles, coupled with Google’s near-monopoly status, makes this segment a sustainable cash generator for Alphabet.

Image source: Getty Images.

3. Meta Platforms

If there’s such a thing as a logical choice to surpass Nvidia’s market cap in the coming three years, social media titan Meta Platforms (META -1.84%) certainly fits the bill.

Meta is an ad-driven business — even more so than Alphabet. Whereas the latter generated 74% of its net sales in the March-ended quarter from advertising, Meta’s social media destinations brought in just shy of 98% of its $42.3 billion in total revenue from ads in the first quarter.

No other social media company is particularly close to attracting the 3.43 billion daily active people that Meta averaged in March 2025. Having ultra-popular platforms, including Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, Threads, and Facebook Messenger ensures that businesses will pay a premium to get their message(s) in front of users.

Meta Platforms is also sitting on an enviable treasure chest of capital. It closed out March with $70.2 billion in cash, cash equivalents, and marketable securities, as well as generated north of $24 billion in net cash from operations in the first three months of 2025. This cash affords Meta the luxury of slow-stepping the development of potentially game-changing innovations, such as the metaverse.

4. Visa

Though it’s the longshot on this list, based on its current market cap of “just” $666 billion, payment facilitator Visa (V -0.08%) has the necessary catalysts to leapfrog Nvidia, when combined with the latter’s headwinds.

Visa’s sustained double-digit sales and earnings growth rate is a function of its being the dominant player in payment processing domestically, as well as having a potentially multidecade expansion runway in overseas markets. According to data collected by eMarketer, Visa handled about $6.45 trillion in credit card network purchase volume domestically in 2023. This was nearly $2.4 trillion more than No.’s 2 through 4 in market share, combined.

Aside from generating consistent merchant fees in the U.S., cross-border payment volume has been continually growing by a double-digit percentage. Visa has the capital and cash flow to organically or acquisitively enter faster-growing (and chronically underbanked) emerging markets.

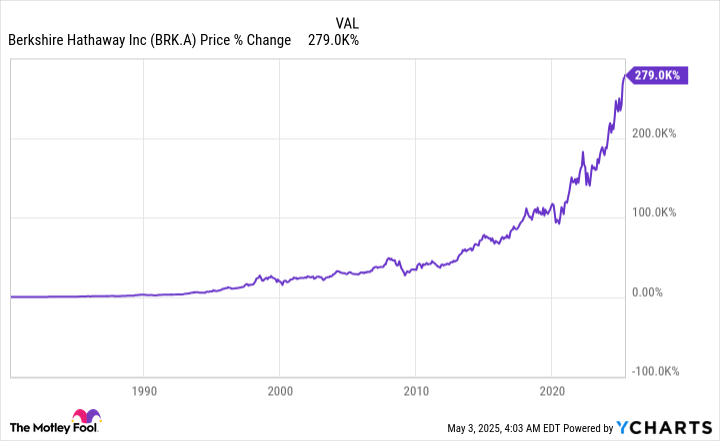

Berkshire Hathaway’s Class A stock (BRK.A) has delivered a nearly 20% annualized return spanning 60 years. BRK.A data by YCharts.

5. Berkshire Hathaway

Last but certainly not least, I fully expect the steady tortoise to beat the hare. While Nvidia’s stock went parabolic in 2023 and 2024, it’s Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A 0.06%) (BRK.B 0.18%) that’s managed a nearly 20% annualized return over six decades. If Berkshire stuck to this trajectory, it could become a $2 trillion company by the midpoint of 2028.

One of the reasons Berkshire Hathaway is such a success is Buffett favoriting cyclical businesses. Whether it’s companies he’s acquired or invested in, the Oracle of Omaha favors businesses that ebb-and-flow with the U.S. economy. Buffett rightly recognizes that, even though recessions are inevitable, economic expansions last significantly longer than downturns. Thus, he’s positioned Berkshire’s investment portfolio and five dozen owned businesses to take advantage of these lengthy periods of U.S. growth.

Additionally, Warren Buffett loves putting Berkshire’s cash to work in companies with robust capital-return programs. Berkshire Hathaway should have no trouble collecting in excess of $5 billion in dividend income over the next year.

In The Power of Dividends: Past, Present, and Future, the researchers at Hartford Funds, in collaboration with Ned Davis Research, showed that dividend stocks crushed non-payers in the return column over the last 51 years (1973-2024): 9.2% (annualized) for dividend stocks vs. 4.31% (annualized) for non-payers. Relying on dividend stocks suggests Berkshire’s investment portfolio is going to outperform over the long run.

Suzanne Frey, an executive at Alphabet, is a member of The Motley Fool’s board of directors. Randi Zuckerberg, a former director of market development and spokeswoman for Facebook and sister to Meta Platforms CEO Mark Zuckerberg, is a member of The Motley Fool’s board of directors. John Mackey, former CEO of Whole Foods Market, an Amazon subsidiary, is a member of The Motley Fool’s board of directors. Sean Williams has positions in Alphabet, Amazon, Meta Platforms, and Visa. The Motley Fool has positions in and recommends Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Berkshire Hathaway, Meta Platforms, Microsoft, Nvidia, and Visa. The Motley Fool recommends the following options: long January 2026 $395 calls on Microsoft and short January 2026 $405 calls on Microsoft. The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.